Part Two (of Two)

Un Sabor De Flamenco (One Flavour of Flamenco)

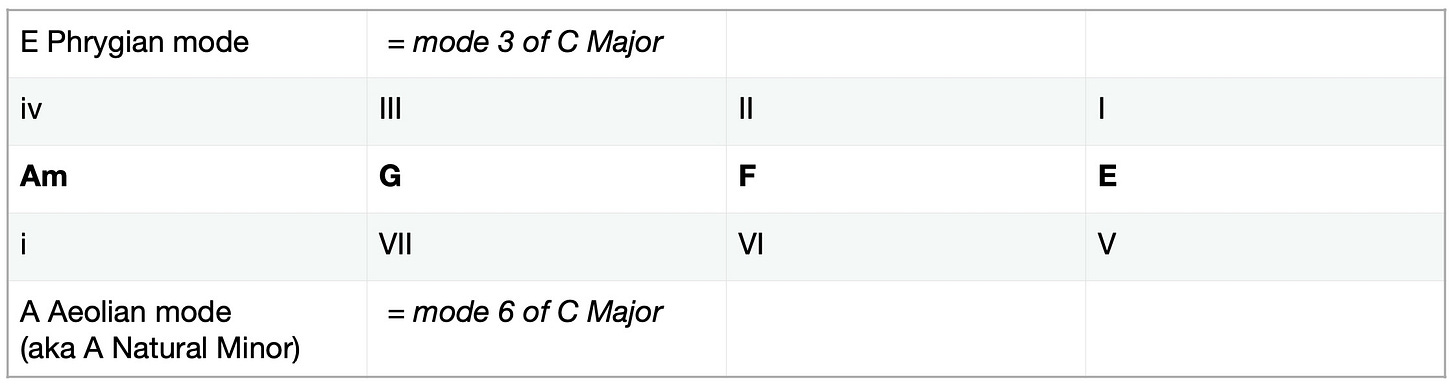

In part one The Andalucían Cadence chord progression and the ‘Por Arriba’ Flamenco Scale were introduced and explained.

The primary purpose of part two is to introduce and explain some chord variations and additional chords that can be used with The Andalucían Cadence Por Arriba progression to further increase the Flamenco flavour.

To briefly recap:

(You may find this Scale and Mode Spellings resource valuable whilst reading this).

The Andalucían Cadence Por Arriba is specifically this chord progression:

Am G F E

By definition, all the chords in this article will relate to playing in the following key centres:

E Phrygian Dominant

E Phrygian

A Harmonic Minor

Why?

Because The Andalucían Cadence Por Arriba can be viewed both as:

A perpetually repeating modulation between the Phrygian mode of C Major (E Phrygian) and the Aeolian Mode of C Major (A Natural Minor).

And:

A perpetual modulation in between E Phrygian mode (with a G natural, not a G sharp) and E Phrygian Dominant mode (with a G sharp, not a G natural).

Diatonic Major Mode 3 Phrygian

1 - b2 - b3 - 4 - 5 - b6 - b7

which for E Phrygian is:

E - F - G - A - B - C - D

Harmonic Minor Mode 5 Phrygian Dominant or Phrygian ♮3 (aka Spanish Gypsy Scale)

1 - b2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - b6 - b7

which for E Phyrigian is:

E - F - G#- A - B - C - D

If you play A Harmonic Minor but instead of starting on point one (A) you start on point five (E), you get E Phrygian Dominant

Harmonic Minor Mode 1 Aeolian #7 aka Harmonic Minor

1 - 2 - b3 - 4 - 5 - b6 - 7

which for A Harmonic Minor is:

A - B - C - D - E - F - G#

There is a nine-note Flamenco scale, called the ‘Por Arriba’ Flamenco Scale, that combines mode scale notes from E Phrygian and E Phrygian Dominant (and therefore also from A Aeolian #7 aka A Harmonic Minor). Most of these notes are also shared with the A Aeolian mode (aka A Natural Minor). And also there are notes from the E Aeolian #7 mode (aka E Harmonic Minor), in particular, it adds an entirely new note, the Major-seventh leading note, D#.

The ‘Por Arriba’ Flamenco Scale.

1 - b2 - b3 - 3 - 4 - 5 - b6 - b7 - 7

which relating to E Phrygian is:

E - F - G - G# - A - B -C - D - D#

Some background…

Before starting with chords, I would like to mention very briefly in passing (because it’s a huge topic and there are so many resources online that go deep into the is topic) the history of the tradition of Flamenco guitar playing. At the very least, it must be around three hundred and fifty to four-hundred years old. Most likely more. It’s not totally historically clear if there was a precursor to the guitar in what became known as Flamenco, however more than likely there was some kind of stringed instrument being used by the ‘Gitanos’ — Andalucían Roma Gypsies, the originators of Flamenco — perhaps zithers or lyres or something homemade, based upon — just for example — stringed instruments that somehow made it across the Straits of Gibralter from the nomadic Berber Sahara desert tribes.

As far as I know, there were no portable keyboard instruments three hundred years ago. Something similar to a harmonium would not have appeared until perhaps the nineteenth century, and, again, as far as I know, this kind of instrument did not feature in the Flamenco tradition. So, the main source of harmony and melody in traditional Flamenco music would have been voice and guitar (or some other stringed instrument).

The key point is that Flamenco was/is still a syncretisation of musical cultures. You can clearly hear the fusion of Eastern European folk with its rich polyrhythms and Indo-Asian microtonality, with North African Berber and Moorish melodies and rhythms. All of this is again fused with and influenced by European Art music, which developed into diatonic harmony. It’s all there — and much more. It’s so rich. It’s so old. And yet it’s still so fresh.

When people start to ramble dogmatically into the WOKE topic of ‘cultural appropriation’, well, the topic of Flamenco is one potent antidote to their misguided venomous credo. Flamenco's deep, rich and long history demonstrates so clearly how music simply knows no borders and boundaries and is a testament to the constant melting pot of cultures, their ideas, their flavours and their musical sounds. Especially this is true in geographic regions where cultures overlap — and Andalucía is a prime example of this. Especially crossroad cities like Sevilla and Córdoba, where people from all over Spain, Europe, North Africa and beyond came into very close contact with one another.

And of course, Flamenco has influenced so many other genres, too many to mention in-depth — classical, blues, and rock, just to name a few. Just for example, you can clearly hear The Andalucían Cadence chord progression in songs like Ray Charles’s ‘Hit The Road Jack’ and the Stray Cats’ ‘Stray Cat Strut’.

The Malagueña

Perhaps (arguably) the most well-known Flamenco chord progression is The Andalucían Cadence. And perhaps the best-known example of this progression is the traditional theme, the Malagueña, probably first made famous by Andrés Segovia’s piece by the same name.

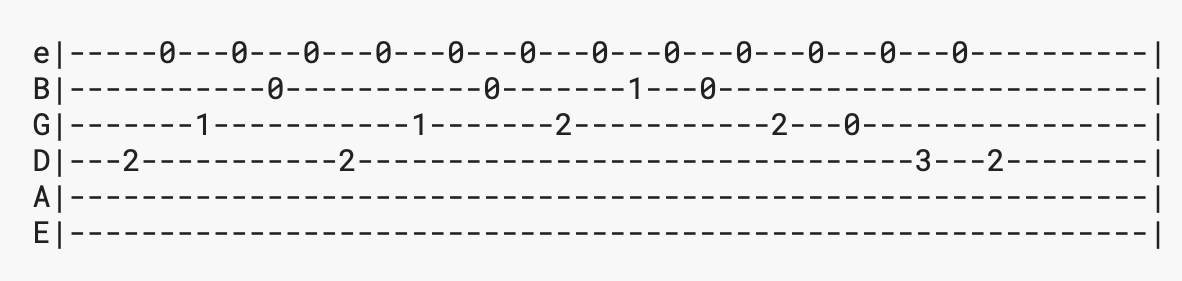

More or less, the traditional Malaguena theme is a four-bar repeating pattern in triple-time. It starts on an E Major chord, changes to an A minor and then passes through a G Major and a F Major chord back to an E Major.

Like this:

Each note is an eighth-note/quaver, so 1 + 2 + 3 + 1 + 2 + 3 + etc

The thumb plays the melody, whilst the index finger plays the open-e.

Below is one of my favourite interpretations/variations of the Malagueña theme, by the great José Feliciano.

The Compas

And of course, we cannot talk about Flamenco without at least mentioning its rhythms, which is an integral part of Flamenco. It’s an immense topic, and not for now here in this article. Suffice it to say that Flamenco's rhythmic system is complex, multilayered, multitimbral, and polyrhythmic — it’s definitely not just straightforward four-four time!

Just one example is the Flamenco ‘Compas’ — a traditional repeating twelve-beat rhythm pattern, for clapping and/or percussion (but mainly clapping). There is an emphasis on beats 3, 6, 8, 10, and 12 - like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Maybe try it, maybe with six beats on an E Major chord and six beats on an A minor chord.

Just for your information, quite often you’ll hear Flamenco clappers start this rhythm with two extra accented beats, so:

1 2 — 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Also, it’s quite usual to occasionally add these same accented two-beats in between twelve-beat patterns. So you end up with:

1 2 — 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 — 1 2 — 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 etc

Honestly, I don’t know how the clappers know when to add these extra two accented beats. They all seem to know when to do it but it does not seem to follow any pattern. I’ve asked about it, however as yet I’ve had no explanation that clarifies it — Flamenco musicians together just seem to naturally intuit when to do it! ¡Olé!

Chords for Flamenco Flavour

What is Flamenco flavour? Words that come to mind are: exotic, dark, moody, sad, wild, Spanish, Latin-American, melancholy, and bittersweet. There’s a lot of suffering and drama. At once everything seems hopeless yet hopeful. There’s an almost constant tension and release. A dissonance that always resolves…

And you feel and see this everywhere in everyday life in Andalucía — people talking to one another seemingly heatedly, with a lot of hand gesticulations, and shoulder shrugging, it looks like it could be an argument, but actually, everything is totally ok, just friends talking, and in the end it’s all smiles and laughter, hugging and back-slapping…

To remind… my focus here is The Andalucían Cadence Por Arriba, specifically this chord progression:

Am G F E

So, by definition, all the chords in this article will relate to playing in the following key centres:

E Phrygian Dominant

E Phrygian

A Harmonic Minor

Four-step Chord analysis process

The key aim is to use the chord progression that you already have (so here: Am, G, F, E), and explore how you can develop, adapt, embellish and/or vary that progression.

The four-step process I’m about to outline below could be used for more or less any chord progression/section (for example, a verse, a chorus, a bridge) of any song or instrumental piece. Its merits are that you break out of the box of just playing the same old chord shapes. As such, it can form the basis of a much more inspiring rhythm guitar part, and/or form the basis of an improvisation.

More or less my four-step process is as follows:

I harmonise the scales of the key centres most closely related to the chord progression I’m focussing upon.

I experiment with different chord voicings in various positions on the neck. In particular (and especially with this flavour of Flamenco) I look for open chords (so chords that include one or more open/unfretted string/s).

I look for chord extensions, variations, and substitutions.

I look for/experiment with chordal relationships.

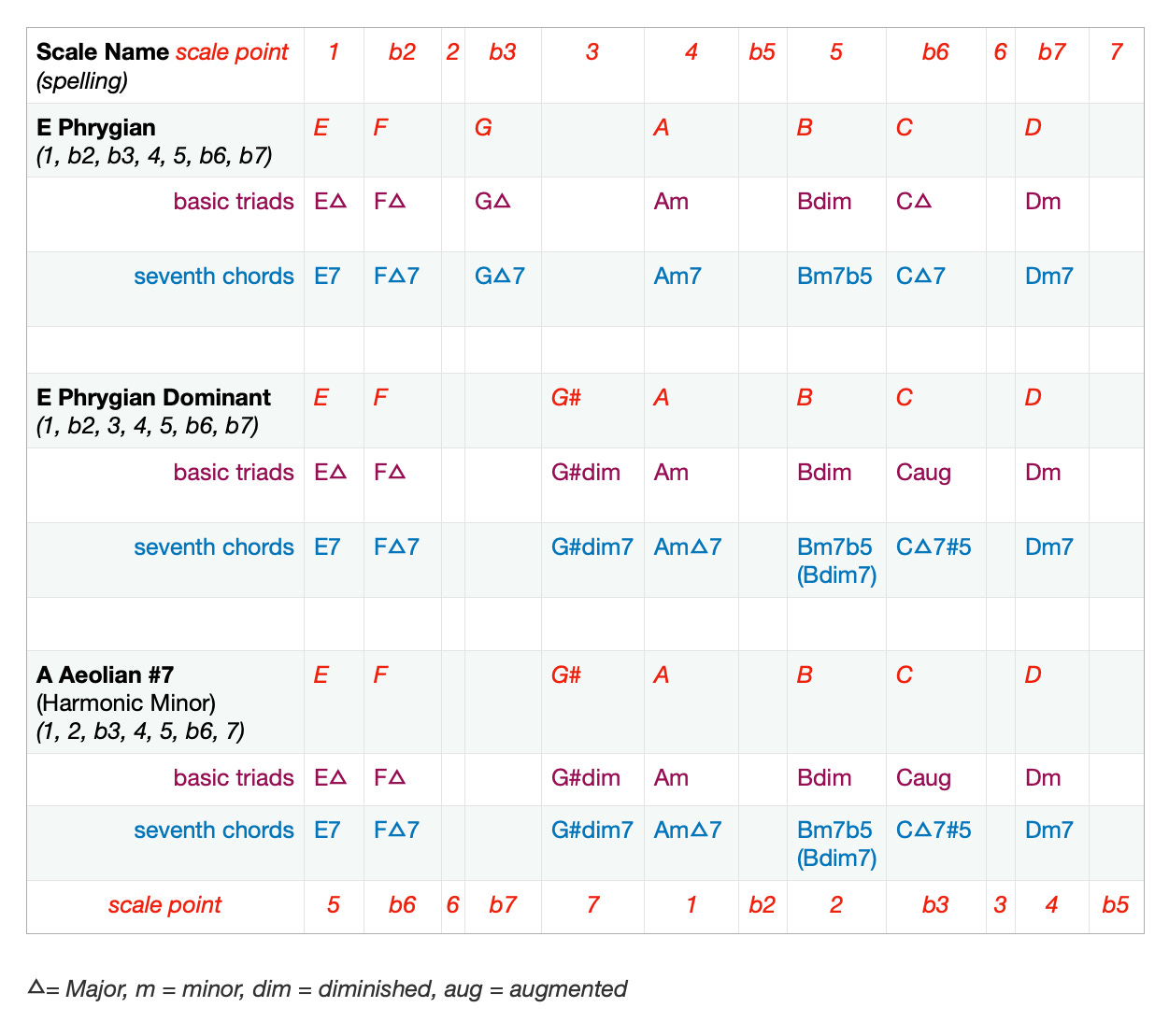

1. Harmonise the Scales

In part one of this article we pinned down that The Andalucían Cadence Por Arriba (so Am, G, F, E) related directly to three scales, namely E Phrygian, E Phrygian Dominant, and A Harmonic Minor (aka A Aeolian #7).

My first step would be to harmonise each point of all three of these scales both in terms of basic triads (so root, some kind of third, some kind of fifth) and seventh chords (so basic triads with some kind of seventh).

Why?

Because this will give more or less a complete palette of available/usable basic chords that can be in some way combined with our chord progression. Also (as will be seen), there will be a lot of basic chords in common shared between each scale.

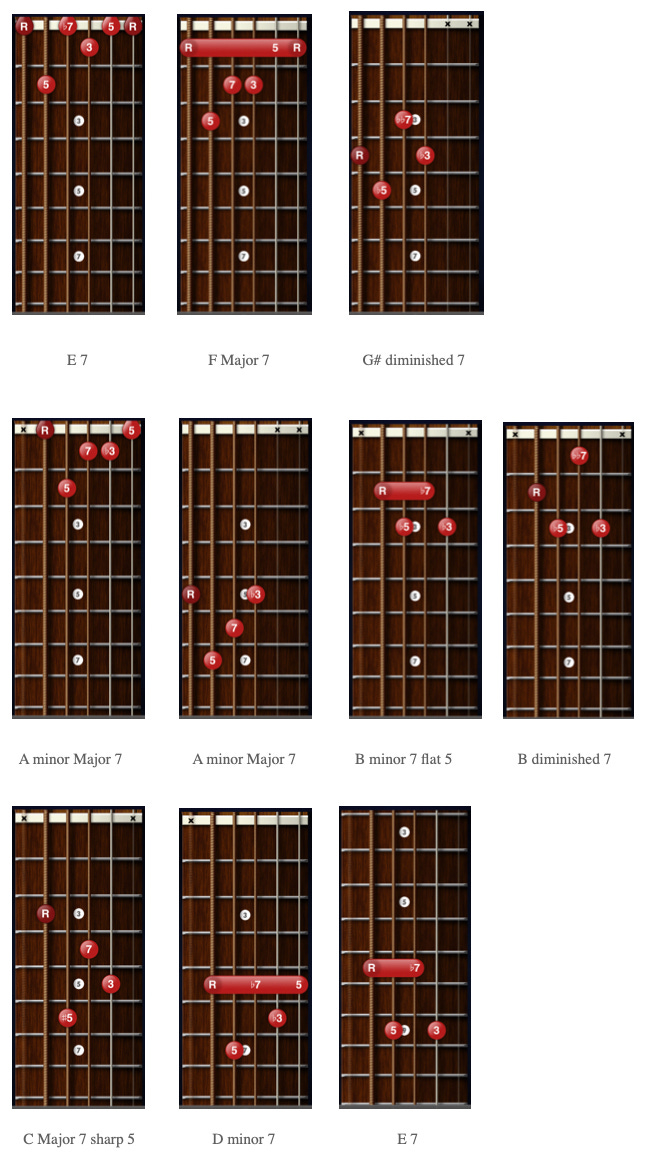

Long story short we end up with a basic palette of nine triads and ten seventh chords. They are:

Triads

E Major, F Major, G Major, G# diminished,

A minor, B diminished, C Major, C augmented, D minor

Seventh chords

E Major7, F Major7, G Major7, G# diminished7,

A minor7, A minor-Major7, B minor7-flat5, B diminished7, C Major7-sharp5, D minor7

(Note that a ‘minor7-flat5’ chord has the same spelling as a ‘half-diminiahed seventh’ chord.)

Here below is a chart that illustrates all these chords. Immediately you will notice that the fifth scalar point for both E Phrygian Dominant and A Harmonic Minor produce two seventh chord options: Bm7b5 has a b7, which is A natural; whilst B diminished7 has a bb7, which is A flat, which is enharmonically equivalent to G sharp. Both A natural and G sharp occur naturally in both the E Phrygian Dominant and A Harmonic Minor scales — hence two chord possibilities.

Immediately we can see that the naturally occurring Phrygian Dominant and Harmonic Minor harmonic chords are exactly the same. The naturally occurring Phyrigian harmonic chords only differ at the third scalar point — the minor-third is G (not major-third, G#).

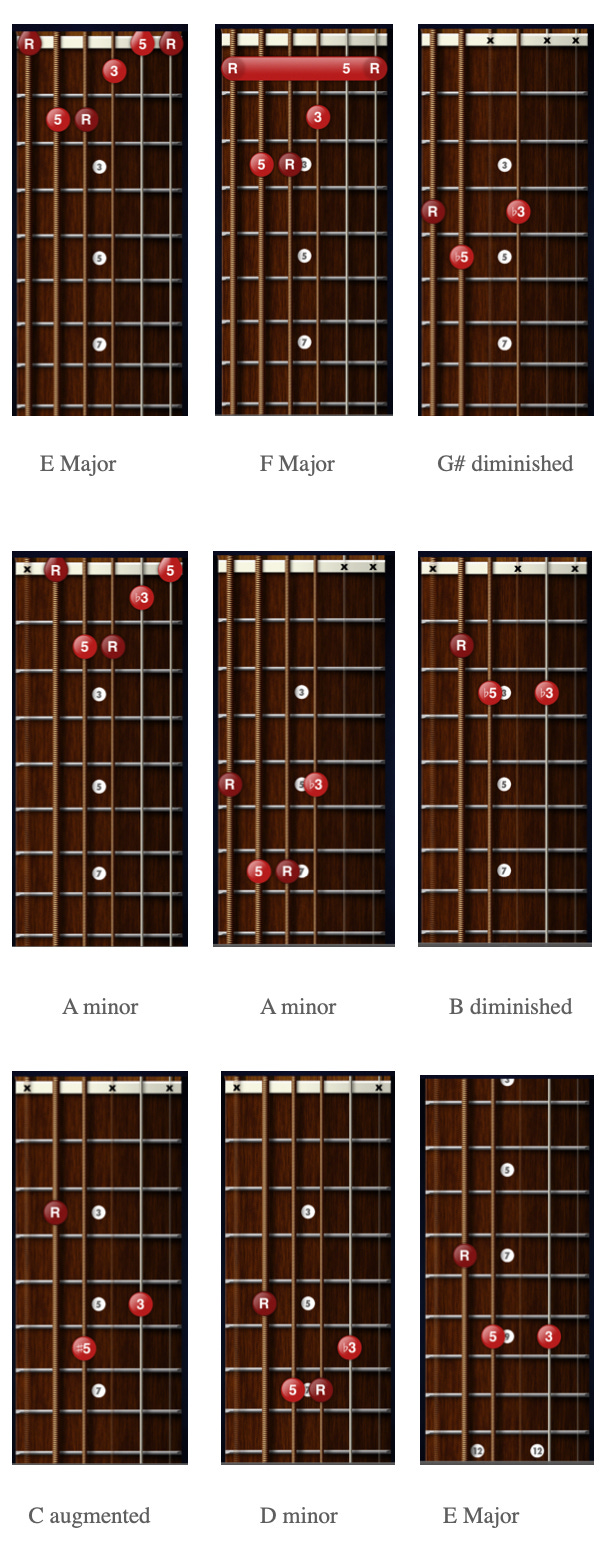

The next question is — how to play these chords?

Well, there’s more than one way to skin a cat!

What I propose here, is to show you one possible way to play the harmonising chords of E Phrygian Dominant. What’s clear is that each chord I show you will have several other possible ways to play it in different fretboard positions. And of course, you could simply strum these chords or you could finger-pick them using several different patterns, or a combination of strumming and picking. The range of possibilities is immense. So, it becomes quite easy to break out of simply playing a standard chord at the nut, like E Major (022100) or A minor (x02210).

Basically, I urge you to explore all this deeply yourself — as I say here I am just going to provide one set of triad chords (and also the seventh chords) for one scale — E Phrygian Dominant. You’ll recall that these will be the same chords for A Harmonic Minor, but for E Phrygian the chords will be slightly different (refer back to the previous chart)… again I urge you to explore all of this.

The triads are (with seventh chords in brackets):

E Major (E7)

F Major (F Major7)

G# diminished (G# diminished7)

A minor (A minor-Major7)

B diminished (B minor7-flat5 and/or B diminished7)

C augmented (C Major7-sharp5)

D minor (D minor7)

Here are the triad chord shapes. To begin with, to clearly hear the harmony, I suggest that you play them in ascending and descending sequence, very slowly finger-picking all of them in this order: root, third, fifth.

And, here are the seventh chord shapes. Again, I suggest that you play them in ascending and descending sequence, very slowly finger-picking all of them in this order: root, third, fifth, seventh.

2. Chord Voicings

Now we have a basic chord palette for E Phrygian Dominant. Remember, the goal here is to explore how to develop, adapt, embellish and/or vary our chord progression: Am, G, F, E.

The next step is to experiment with different chord voicings in various positions on the neck. And, in particular (and especially with this flavour of Flamenco), to look for open chords (so chords that include one or more open/unfretted string/s).

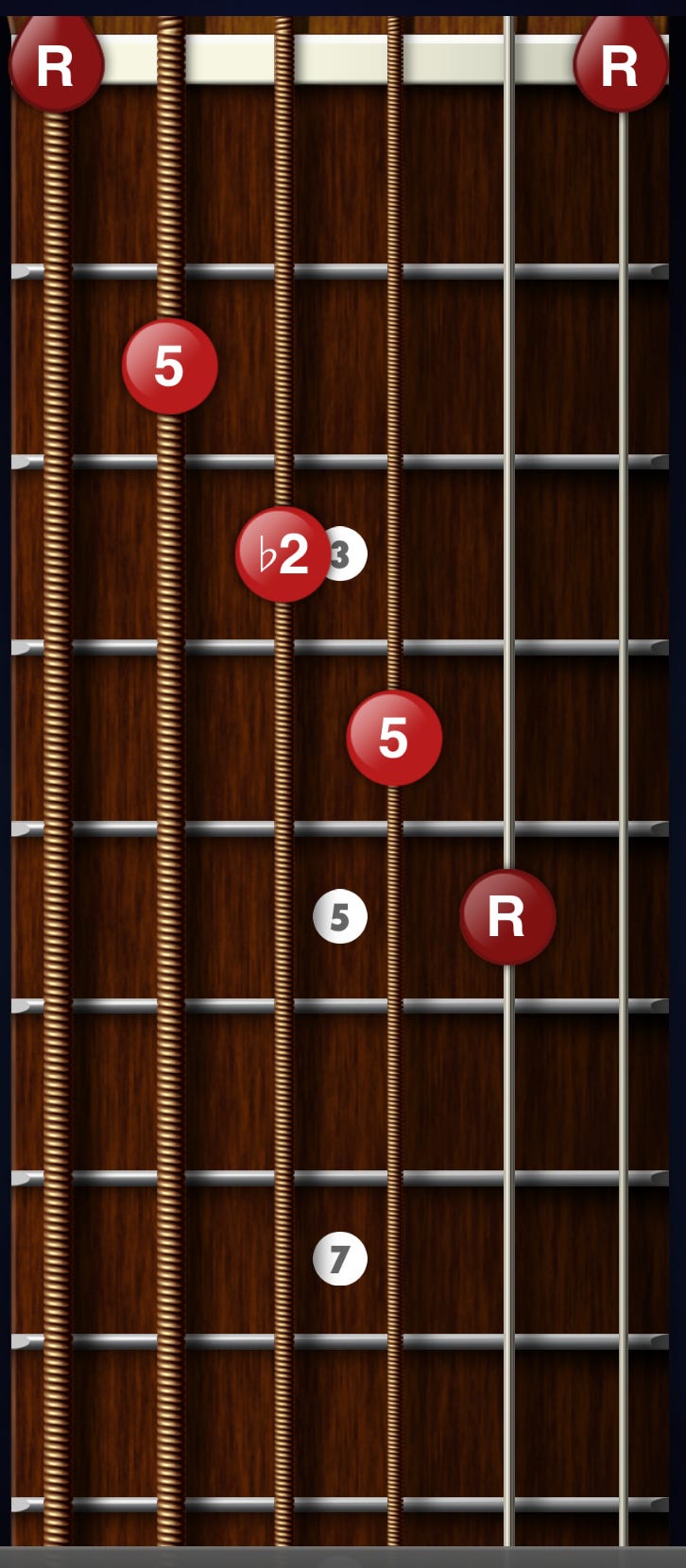

To get you started, and to demonstrate this, here below are a few ways to play A minor-based and E Major-based chords. It’s not a definitive list, not by any means — there are still many more ways to play these chords, but you get the idea. You can do a similar exercise with any of the triads or seventh chords in the E Phrygian Dominant chord palette.

3. Chord Extensions, Variations, and Substitutions

Next, we can start to add some specifically Flamenco-sounding chord extensions and variations.

But first — the topic of chord substitution is big! Here, in this article, I am only going to very briefly glimpse at it, and give one simple example, just so you can see what it’s about. I’ll do that now.

Have a look at the spelling of the F Major 7 chord (personally I find this easier in front of a piano or keyboard) — it’s F, A, C, E.

F Major 7 is the II 7 chord in E Phrygian Dominant, and the VI 7 chord in A Harmonic Minor.

If you remove the root not (F) you are left with A, C, E — which is our A minor chord.

Therefore, if at some point you want to play F Major 7, and you know that, for example, your bass player is going to be playing an F, then you can substitute F Major 7 with an A minor chord — the result will be F, A, C, E, our F Major 7 chord.

Especially you could play A minor add b6 — spelt A, C, E, F, which is also the spelling of the first inversion F Major 7.

That’s a whirlwind tour, just one simple example, of the vast topic of chord substitution!

Now we start looking at some chord extensions and variations.

An extended chord is (usually) a triad or seventh chord with some additional notes added.

Probably the best example in Flamenco is the add b9 chord for the I chord of Phrygian Dominant, so here that would be E add b9 (for example, 023100)

Try going backwards and forwards between a regular E major (022100) and this E add b9 (so an added F) — you’ll immediately hear this famous dark sad Flamenco flavour.

The next step is to find some variations of this extended chord, just to experiment with. For example:

‘Variations’ is — I suppose — another way of saying voicings (see the previous section ‘Chord Voicings’), yet it can also mean chords that perhaps omit just one note, like this chord below, E add b9 with no 3rd.

So the goal here is to look at our basic chord palette for E Phrygian Dominant and see which chords could be extended and how. One last example (and we already saw this chord in the ‘chord voicings section) is Am9 aka Am7 add 9 (spelt 1, b3, 5, b7, 9):

4. Chordal Relationships

Now we have quite a large selection of chords that we can play around with. The next step is to experiment with small groups of these chords, to see what works well together, also perhaps search for chords that sound similar, and generally try to discover what you like — basically to start building a chordal vocabulary that you can use to express ideas based upon the flavour of The Andalucían Cadence.

Below, in no particular order, are some (by no means a complete list) chordal relationships and observations to consider. You will see that in the end, you will have all of these fragments, like pieces of a kid’s construction game, that you can combine together in almost endless ways…

In the previous section (‘Chord Extensions, Variations, and Substitutions’) we already looked at one very simple yet effective chordal relationship: the I (of E Phrygian Dominant) to I b9, so E Major to E b9.

I like these open chord variations, in particular, this semi-tone change between E 5 (079900) and E 5 add b9 (079.000); and also the semi-tone change between E 7 (079790) and E 7 b9 (089790) — maybe resolving another semi-open A minor chord (x07555).

There is also something similar using this open chord version of F b5 with no third (x89.007) resolving to this open variation of E 5 (0x9907).

Another very obvious chordal relationship — perhaps the main one here — is Am to E, so i to V in A Harmonic Minor, and iv to I in E Phrygian Dominant (and E Phrygian).

Another well-used Flamenco flavour is a semi-tone move between, for example, E major and F Major. You can quite effectively just go back and forth between these two chords. For even more play an open variation of the F chord, like F Major 7 #11 (033200)

There are several other semitone changes in between chords that I personally like, below I’ve listed a few.

Dominant 7 down a semitone to diminished 7, so in E Phrygian, C 7 to B diminished 7 (maybe resolving to A minor, or perhaps A minor 7)

In E Phrygian Dominant, G# diminished up a semitone to A minor (and also using seventh chords, so G# diminished 7 up to A minor Major 7).

F#m7b5 (x9.09.0x) down a semitone to F Major7 (x8.09.08), resolving down a semitone to E major (x79997) or E 7 (x79797) — then perhaps follow this sequence with something starting on A minor 7 (575555 or 575585).

When playing A minor (x02210), hammering off and on, on the B string, between the C (a minor third) and the B (a Major second) notes (so x02210 to x02200 which is technically A suspended 2nd). It sounds very similar to the change between E major and E add b9.

When Playing F Major flattening the fifth (1232xx), then resolving to E Major.

Next, let’s focus on the G chord. G does NOT naturally occur in the E Major scale, the E Phrygian Dominant scale, or the A Harmonic Minor scale. It does occur in the E Phrygian scale (scalar point 3) and the A Natural Minor scale (scalar point 7). This means that the seventh chord of the G chord in our Am, G, F, E progression (The Andalucían Cadence) would best be G Dominant 7 (G B D F).

The V7 to I in E Phrygian Dominant is B diminished 7 (or example x2313x or x23131) to E Major. It is a very melancholic-sounding change. You can also extend the V7 chord to B diminished 7 add 11 (for example x23130)

Note that the B diminished 7 is very similar in sound to E b9 (mentioned above) — it’s almost identical!

Personally, I like the change from A minor to F (or A minor 7 to F Major 7). I also like A minor 9 (575557) to F Major 7 (x8.09.08 or x87555 or 1x2210)

A variation of this is A minor through F major resolving to E Major. Instead of a straightforward A minor (x02210) I sometimes play a variation, A suspended 2 add #5 (x03400) to F Major 7 #11 (133200) to E Major (022100)

You could easily continue with this line of experimentation — basically, just find what you like…

Finally, I recommend that you take the time to try transposing EVERYTHING covered in both of these articles to another key and experiment with all of it again, for example, transpose to A Major — so E Phrygian Dominant up five semitones to A Phrygian Dominant. The mental gymnastics is worth it.

In part one of this article, I mentioned a local Flamenco guitarist, José Ramon, whom I met here in Málaga. He and two other local Flamenco artists performed locally last Saturday. I said I’d film him on my phone to provide a real taste of authentic local Flamenco. Oh, and by the way — for the record, I think José practices occasionally! Below or two clips. The first is solo guitar with clapping. The second is guitar and voice with a dancer.

In your hands — both of them…

Almost everything, in both parts of this article, has been about the left-hand, about chords and scales. I have not yet touched upon, not even for a sentence, the right-hand.

Why?

A. I know so little about Flamenco's right-hand technique, for example, (and in particular) rasguedo, or Flamenco finger-picking patterns and styles.

B. Time investment! To master or even come close to mastering these right-hand techniques requires a considerable chunk of time.

Personally, I am happy just being able to simulate something close to a Flamenco guitar flavour, and for this one mainly needs to understand the left-hand — the chords and scales. For most intermediate to advanced guitarists grasping the basic left-hand theory and practice does not involve such a huge time investment, maybe a week or two, at most a month or so.

So the left-hand feels like a good place to start. If — after learning a few progressions, chords and scales — Flamenco really grabs you, then a more realistic decision about investing time in mastering the right-hand techniques can then be made.

Again, here it feels appropriate to remind you that I am not a Flamenco player or aficionado, so please check everything I have laid out here, more than likely there are errors and maybe even misinterpretations.

Enough said.

Hopefully, with just this short glimpse into just one Flamenco chord progression, a Flamenco scale, and some additional chords, you can start to appreciate a little more about the totally unique Flamenco melodic harmonic system, and its simple yet rich, complex yet subtle unique flavour.

Please note: I have another infotainment channel on Substack, called Unleashed & Unlimited, where I post podcasts, articles and content unrelated to music.🖋🎥🎙